“Amphibious loss?” inquires my bewildered friend, sipping his coffee. “What’s that?”

I reconsider the joke brewing in my mind about missing salamanders. “Ambiguous. It’s unresolved, ongoing grief,” I explain, summarising the workshop I just attended. “A grief without closure.”

Psychologist Pauline Boss, PHD, coined the term ambiguous loss in the 1970s, and dedicated her life’s work to exploring it. I recently attended a workshop on the topic by Wellways, a Brisbane carer’s organisation. It was gratifying to learn a name for something so ostensibly nameless - the feeling I’ve had watching my mother’s physical and mental health decline. At times, it’s been difficult to explain to others.

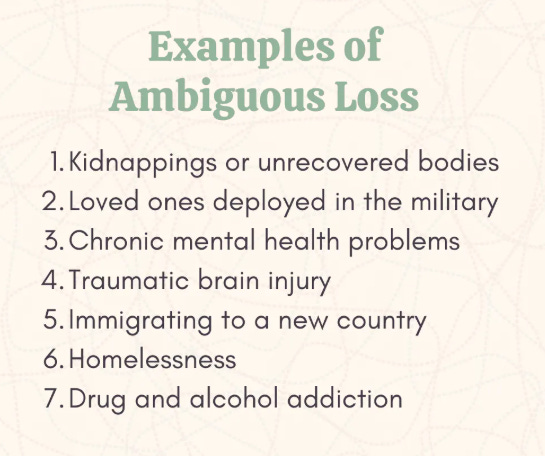

Ambiguous loss isn’t limited to carers of sick loved ones. It’s an apt description for so many situations in life. We’ve likely all felt it before, though perhaps not been aware there was a term for it.

Ambiguous loss describes a grief without the resolution of death - a complicated, frozen state that elicits complex emotions. It can apply when a loved one is physically lost (for example, a soldier missing in action, someone who goes ‘no contact’) without confirmation that they’ve died. This kind of grief can also result when a loved one is still physically present, but seems psychologically missing - in cases such as cognitive decline, dementia, mental illness, addiction, etc.

Those who know, know. My mother is not the mum I remember. There’s a je ne sais quoi feeling that arises when interacting with somebody who used to be…different. Although I’ve been blessed with wonderful life events, especially lately, my feelings of joy or excitement about them are often tempered by guilt and sadness - a confusing, complex cocktail of feelings.

Living with ambiguous loss is like living with ghosts swirling around you.

Most of us have had the experience of grieving people who are still living - during romantic breakups, when we’ve grown apart from friends - or of grieving parts of our lives that are now over.

Moving to a new city or workplace can stir up ambiguous loss. The places and the people left behind still exist, yet the grief can hover for years.

Pregnancy loss can also be ambiguous - grieving a person who may never have ‘existed’ in the first place, but who nonetheless touched your heart.

Even having a healthy baby can elicit a kind of ambiguous loss. Despite loving their child dearly, parents may feel grief over the fact that they’ll never again be the carefree, child-free people they once were.

Here are some examples of times I’ve felt these feels -

Growing up with my father mostly absent

Moving away from most of my family in late childhood

Experiencing multiple breakups

My aunt and my grandmother both getting sick, respectively

Losing friends to conspiracy theories / weird belief systems

Having friends disappear into drug addiction

Deciding to no longer play/ perform in bands

Weathering traumatic events (grieving the person I might have been without them)

Having a miscarriage

Losing friends and partners to screen time (being physically near someone whose mind is often a million miles away)

An ambiguous loss can relate to anything, really - it’s simply a grief that doesn’t have a tidy resolution such as death. Sometimes the grief relates to a loved one, and sometimes it relates to oneself - grieving a ‘you’ that you’ll never get to be again.

How, oh how, are we to grapple with such amorphous, ambiguous, amphibious loss?

In her book Loss, Trauma, and Resilience: Therapeutic Work with Ambiguous Loss (2006), Pauline Boss mapped out six therapeutic goals for treating ambiguous loss.

Using the six pillars of resilience through ambiguous loss, Boss theorises that recovery is possible - though the patient will probably have to embrace change to do it.

1. Finding meaning* - Firstly, find your own meaning in the loss. This may mean finding a way to understand what happened, or even creating your own ritual of closure.

2. Tempering Mastery - Accept the uncertainty and lack of resolution - accept what you can’t control.

3. Reconstructing Identity - Re-establish your sense of self, despite the ambiguity. The situation has probably changed you. Who are you now?

4. Normalizing Ambivalence - Acknowledge the complexity of emotions during loss. (You’re not crazy. The situation is crazy.)

5. Revising Attachment - Adjust the relationship, if applicable, to account for the uncertainty. For example, in my case, I’ve had to accept that I’m more of a mum to my mother now than she is to me.

6. Discovering Hope - Find renewed purpose and hope, despite the uncertainty - find hobbies, joys and pleasures in your life that have nothing to do with the situation.

*A woman in the workshop I attended offered a great example of finding meaning. She told our group that she’d been experiencing ambiguous loss for years due to a situation in her family (we didn’t pry about what the situation was). Over the years, she said, she’d had trouble with falling out of bed - a lot - during sleep. She’d injured herself more than once.

When she finally realised that she’d been having repetitive dreams of chasing people, or of running away from people chasing her, it clicked for her. She realised that there were certain people in her family she just couldn’t deal with, people whom she needed to ‘escape’. When she figured out the meaning behind her dreams, the dreams ceased, and the falling-out-of-bed accidents stopped.

The tough thing about ambiguous loss is that it’s…ambiguous.

My friend’s misnomer of amphibious loss may not have been so far off the mark. It shares the ‘ambi’ prefix, meaning on both sides. Amphibious: related to, or living in, both land and water. And-both, not either-or.

According to the workshop I attended, becoming comfortable with the ambiguity of complex losses is crucial to recovery.

Us humans are not wired to think of things in an ‘and/but’ way. We prefer things tidy, black or white. But ambiguous loss means living in a grey reality. Two things can exist at once - joy and misery, for instance. A person you loved may still exist, but no longer as the same person you loved. That’s a hard, but necessary, pill to swallow.

Ultimately, a complicated loss leads to complicated grief. It takes work to understand and to come to terms with what’s happening. And there will undoubtedly be a sense of madness attached to what’s going on.

There may be no certainty of the situation or how it’s going to turn out. There may be times when things seem to be going well, and then all hope can be dashed. Certain days may be more difficult than others.

Ambiguous loss necessitates a long distance run. You can think you’ve made a lot of progress, but then a glimmer, a memory of what was arises, which can drag you right back to square one.

Perhaps my friend was right. Perhaps we must learn to become amphibious to deal with ambiguous loss: to walk on the comfortable solidity of land, and to swim through muddy, slippery banks of water. It’s in the acceptance of both that we’ll be able to heal. We supposedly share an ancient, fishy ancestor with our froggy friends. We had a chance to be amphibious once. Why not try again?