“WTF is wrong with people, Bec??” my friend types to me.

We’re talking about my latest time-wasting obsession: watching the reality show Escaping Polygamy. (A cult documentary will suck me in any day.)

I’ve just relayed my outrage to said friend about the Kingston Clan (a Mormon sect) and their penchant for systematic, incest-ridden paedophilia. Now we’re both depressed and outraged. It’s fun being my pal!

My friend’s wondering is justified. I decide to respond seriously to what is probably a throwaway rhetorical question. What the fuck IS wrong with people, anyway?

“Fear (+ conditioning) = the women. Power (- empathy) = the men,” I theorise, without thinking much deeper about it, without thinking outside the bounds of that religion’s particular mess of gender-based power hierarchies.

Later, I think harder about it all.

I think: power corrupts. We know this. This phenomenon has been reported on - a lot.

But how does it corrupt? And why? Is it really, as I surmised, because power erases our ability to empathise?

I looked into it, and it turns out, pretty much. The Atlantic put it a little differently with the title of Jerry Useem’s 2017 article: Power Causes Brain Damage.

I have never really sought power in my life, but I can recall a time when I briefly flirted with it. In my early twenties, I was named manager of a retail store I worked at.

I’d have described myself as a chill co-worker, before that. My 18 year old co-worker - let’s call her ‘Unreliable Sally’ - never used to bother me. She asked to change shifts around fairly often, was occasionally late, and sometimes called in sick at the last minute when she needed to finish up a Uni assignment. Sally had a fun personality, and I never minded picking up the slack when we were at equal status. I knew she was juggling a lot at home and at nursing school, and she often made up for the slack with a little snack-share, or by staying later than she was rostered. She was a good worker, when she turned up.

My priorities slowly changed once I became manager. Suddenly, I was in meetings with area managers and head office. I was now the one responsible for things like rosters, staffing, budgets and store reports. And Unreliable Sally really started pissing me off.

On a few occasions, I was sharp with her, even mean. I eventually started giving her less and less shifts - even though I knew she needed a certain amount to get by. What was the point, I thought, when she frequently tried to change them around, anyway? Didn’t she understand the pressure I was under? Why wasn’t she appreciating the opportunities I’d given her?! What an ungrateful little bitch!

My uppity manager era may be a tiny example of the brain under the influence of power, as Psychology Today writes. Once I was promoted, I became more concerned with my own self-interests, and lost the ability to see Unreliable Sally the way I used to - as a fallible friend. I wasn’t just working with her anymore, I was responsible for her - and my empathy and patience for her waned. I wanted to project an image of perfection, and her imperfect performance affected my image.

This experience gave me insight into the way people in powerful positions may begin to see themselves: as superior to their underlings. I didn’t really like the person I became, as a manager. Some people do well in powerful positions, but I realised I might not be one of them. I had applied for the position - I had sought it out - so I felt a certain satisfaction when I achieved it. I cared about keeping my new status. Maybe there’s something to that oft-quoted adage of Plato’s: “those who take office should not be lovers of rule”.

In other words, those who seek power are the least qualified to hold it.

I guess we can rule out a lot of politicians as fit leaders, then.

When an individual is in a position of power, as was my experience, they tend to focus more on themselves. Attention is a limited resource, so if one is focusing more on themselves and their own concerns, it follows that they’d have less attention to give to others.

And attention, as it turns out, is crucial to the process of empathy.

Research suggests that physical empathy emerges before the internal, or emotional, experience of empathy. The process might look like this: when we see a friend cry, our facial expressions begin to mimic theirs - we scrunch up our cheeks, we frown, our eyebrows raise - and then, our internal feelings of empathy arise.

But if we’re not paying attention to our friend’s face - or if we’re going through the motions, distracted by our own to-do list of Important Tasks - this process doesn’t happen. Others’ feelings become less important.

Over time, when individuals hold powerful positions - when they’re leaders of cults or companies or countries, perhaps - their spectrum of acceptable self-behaviour widens. After all, most people immediately surrounding a powerful person seek to please that person. Being surrounded by yes-men, none of whom dare forbid said leader anything, would make it seem as though more and more things are fine to do. Thus, that leader’s filter, their moral compass, their questioning process, is lost.

This makes it much easier for powerful people to give into their own selfish impulses.

That Atlantic article Power Causes Brain Damage is a very interesting read, and chock-full of research to support this.

After years of experiments spanning two decades, psychology professor Dacher Keltner found that subjects under the influence of power acted as if they had suffered a traumatic brain injury. They became ‘more impulsive, less risk-aware, and less adept at seeing things from other people’s point of view.’

In other words, more psychopathic.

Neuroscientific research such as Sukhvinder Obhi’s has also demonstrated that having power impairs ‘mirroring’ in the human mind - a process that involves subconsciously imitating other people (something integral to empathy).

Is it any wonder, then, that powerful people often regress to unethical, immoral behaviour?

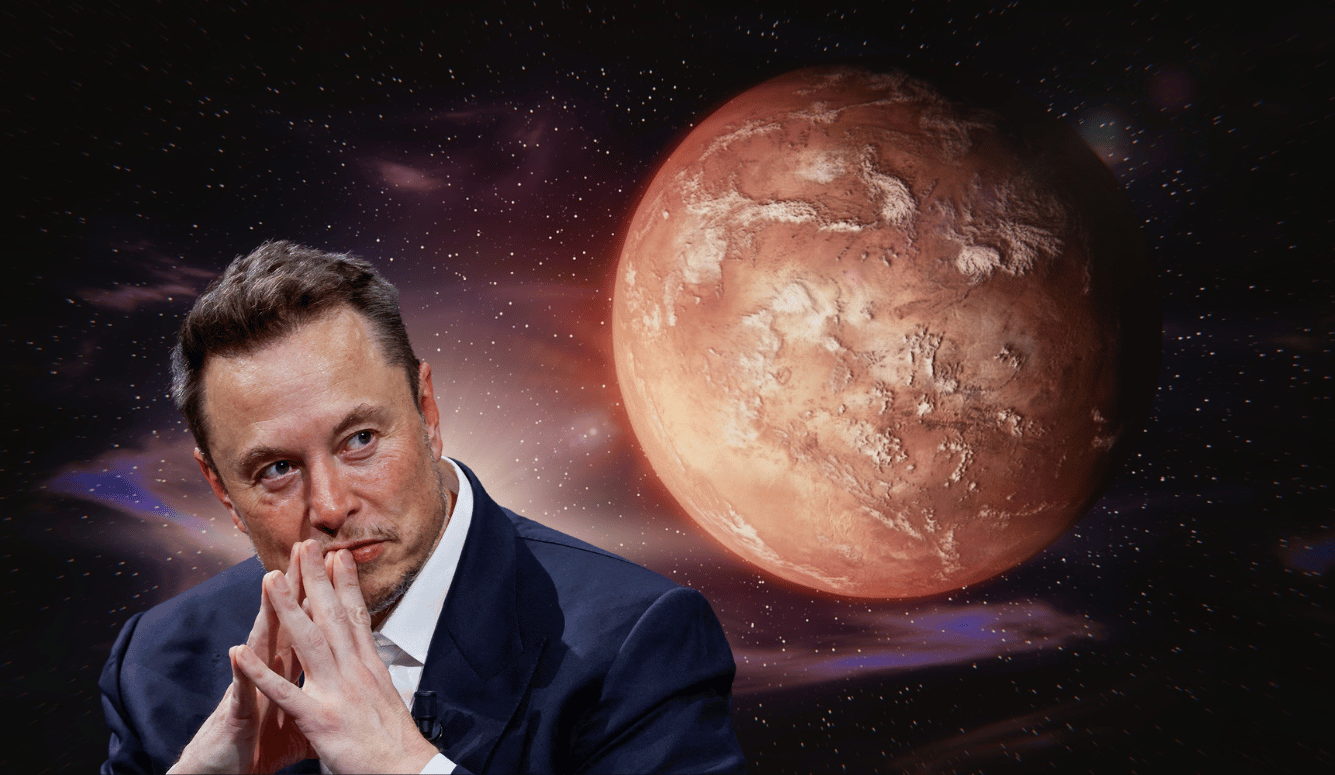

I don’t intend to shrug off the behaviour of sick individuals like the men of the Kingston Clan, or anyone who uses their power to abuse others. Power is no excuse to hurt others. But it seems that power can be a dangerous drug. When unchecked, it seeks only to make itself bigger - to replicate itself, to gain more of itself - and to conquer others. When it has no one left to conquer, it looks to conquer bigger things - sometimes even life, death and the world itself.

As evidenced by my glee at watching the downfall of cult leaders on TV, I’m not a religious person. Yet the timeless story of Lucifer is a great parable for what a person high on power might seek to do. When pride is a person’s sole motivator, what else would they seek to become but a kind of God themselves?

The philosopher Nietzsche saw The Will to Power as something beyond good and evil - he saw it as the driving force behind the very act of living, a continuous striving and becoming. He saw power as the will to overcome resistance. Perhaps, as Nietzsche suggests, power in and of itself is not a bad thing. But research shows it certainly seems to have a corrupting influence on the human soul. Thus, it’s something we should always be wary of.

Most of us regular humans are probably safe from the trappings of extreme power, but it is still worth keeping these concepts in mind. When we’re teaching, parenting, or even just lurking behind our keyboards, leaving a comment for someone on social media, we must be responsible with our power. We must seek not to dominate, humiliate or abuse others, but to operate as if we’re all in the same boat, and deserving of the same rights. Above all, we must remember to empathise. For power, without values underpinning it, without an applied ethical framework, makes people do scary things.