I have a confession to make: the moment of history we’re currently living through scares me. Tackling urgent worldwide problems, such as climate change, financial disparity and human rights, requires collective action.

Collective action requires problem solving. To problem solve, we need to make decisions. To make decisions, we first need to be able to review the facts. That’s the scary thing about this moment of history: many of us are incapable of taking that first step right now.

If you feel unsure of what facts even are anymore, you’re not alone. We seem to questioning the nature of reality at the moment. The metrics we’ve always used to define truth are either no longer valid, or no longer trusted.

It wasn’t always like this. Some philosophers even predicted we’d get here. In this piece, I’ve mapped out three contributing factors to our current predicament, and some thoughts on where we’re heading.

‘Reality’ TV

Reality TV is now the most popular genre of television worldwide. Watching ‘real lives’ unfold onscreen became popular in the early 2000s, and its widespread appeal has grown exponentially since then.

If Reality TV was entirely fabricated, it would be easier to dismiss as pure entertainment. Instead, it’s usually a blend of planned, scripted, edited situations, and genuine emotion, surprises, and spontaneity. It’s easy to understand why this genre ignites such debate amongst its fans about what really happened, and I believe it has accelerated our confusion about what reality is.

We have accepted the label of reality for the highly orchestrated, and sometimes unnatural, situations this genre broadcasts. The constant presence of cameras in reality television (and increasingly, in our daily lives) make it arguable that none of Reality TV is, in fact, reality. One simply does not live one’s life the same way when being watched.

Could the presence of secondary layers of watching give a closer approximation of reality? If we watched footage from a camera filming the camera people making Reality TV - if we saw the editors editing, the directors telling the cast what to say - would that not be more real?

Maybe not, because then we’d have to edit that footage. And even if we didn’t, we’d have to first choose where to place the camera, which is still choosing a point of view. Cameras simply cannot be relied upon to capture reality. By their very presence, they influence it.

Reality TV has taught us some useful lessons about psychology, at least. It’s helped us to realise that, when it comes to human relationships, there are multiple sides to most stories. Even when someone’s clearly ‘the villain’ in a situation, according to basic ethics, their own viewpoint and emotions usually lead them to feel like either ‘the hero’ or ‘the victim’.

By bingewatching our favourite genre of entertainment, we have deeply absorbed reality television’s lessons about subjectivity.

In addition, we’ve become hyperaware of the construction of it. Most of us understand that it’s highly edited in a way that may alter our perceptions.

Some of us have used this relatively new genre of entertainment to increase our sense of empathy, scepticism and self-awareness. But others have absorbed a belief that ‘there is no such thing as objective truth anymore’ - in any facet of life.

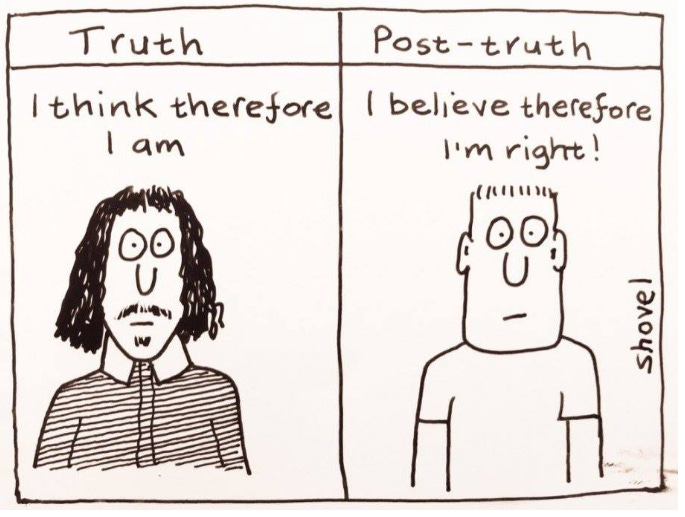

Post-Truth

It might be reasonable to suggest that reality TV, combined with social media, has lead us to the political era we currently inhabit: post-truth. Post-truth (also described as post-reality politics) describes the widespread anxiety we now have about what publicly accepted facts even are.

Social media has fragmented news, once a (relatively) reliable source of fact. Instead of news, we now trust newsfeeds, echo chambers and deliberately viral half-truths. It’s easy to see how we all got so confused; when everyone we know starts parroting something that isn’t true, how can we not fall into the same trap?

This post-truth era has made politics the most segregated and identity-based they’ve ever been - at least in my living memory. The poles have also shifted. Centrists are considered radical leftists, and what used to be the fringe of far-right is now ‘moderate’.

I’m now a dangerous, deluded ‘libtard’ because I believe things like ‘everyone should be able to afford healthcare’ and ‘discrimination exists in a measurable way’.

The era of post-truth makes it almost impossible for me to talk to certain right-wing people in my life anymore, even with empathy and compassion. The chasm did not use to be this wide. I used to have friends with a variety of beliefs, and the more conservative ones actually would consider my points. But empathy and compassion do not work as appeals anymore; Trumpian politics have convinced average people that they’re suckers if they feel for others.

Facts do not work, either. I’m going to generalise, because it’s really been that generalised in my experience: when presented with facts, right-wingers will now dispute them, or claim facts are falsities. If they acknowledge damning data, they will question the bodies that even created the data. They have been so deeply indoctrinated by Fox News-like media that they believe our last bastions of objectivity - science and independent journalism - are as prone to corruption as politics. (Both arenas actually have standards, regulations and inbuilt accountability for their imperfections - but with that mob in the White House now dismantling everything, they might not, soon enough.)

Capitalism vs. ‘globalist conspiracy’. Science vs. anti-vaxxers. Secularity vs. religion. Free speech vs. ‘free speech’.

You’ve seen it. I don’t need to further summarise it. We’re in it, right now.

How did we get here?

Institutional Gaslighting

Propaganda is gaslighting on an institutional level, and it’s cropping up frequently these days. The right wing has capitalised on our post-truth era - anything goes, if you shout it loud enough, no matter how little sense it makes, or how little basis it has in fact. (The fact that something has been said at all now seems to make something a potential fact.)

They know how to do propaganda on the internet now. And a grain of fact mixed with a lot of fiction breeds confusion.

The language we use can help us to understand our reality, and I find it interesting that we’ve recently added gaslighting, a psychological term, to our cultural lexicon. It’s been a frequent topic ever since. It’s made its way into our discussions about relationships, and even into political discourse.

What is gaslighting? It’s an abuse tactic. It’s making someone who’s sure of what happened question their memory, using denial and sometimes more insidious methods. Gaslighting creates an ‘alternate universe’ of truth.

Gaslighting is not the same thing as what’s been shown to us on reality TV shows - two people squabbling over who treated who the worst. Gaslighting requires one party’s intention to mislead.

On a personal level, gaslighting is cruel and manipulative. It can destroy mental health and make one question their own sanity. On an institutional level, it can be catastrophic. It can destroy the health of a society, and make people question if objective truth exists. It can make people do very bad things. It has made them kill each other.

Our newfound obsession with applying the term ‘gaslighting’ to anything and everything lends itself to that myth we have now internalised: ‘there is no objective truth’.

Gaslighting objectively exists, but the problem is that gaslighters know how to turn it around. Most psychological abusers, if you call them out on it, will immediately switch it up and call you the abuser for saying an evil thing like, ‘I see that you’re abusing me. Please stop that’.

Gaslighting begets a pendulum effect. If you call someone out for gaslighting you or feeding you propaganda, even correctly, they’ll just accuse you of doing the same. Swing back, swing forth. No wonder it’s hard for some people to determine truth.

Save us, metamodernism!

I am a person whose hope for humanity has not been entirely crushed. When I wonder ‘where do we go from here?’ I look to art, and then to cultural conversation. I see what many people are making right now, and I feel optimistic. I believe we’re in our metamodernist era, and I like it.

If you’re still with me, I’ll explain what the fuck I’m talking about.

There are certain overarching trends in popular culture and art - well-known examples include the renaissance era, or romanticism. We give these trends names and talk about them, not because they’re tangible things, but because it’s useful to be aware of them. They map public sentiment and the evolution of ideas. They can tell us a lot about where we collectively are and where we’re headed.

From the late 19th century to around the 1950s, modernism grew - experimental, heartfelt, disruptive. From around the 1960s to the late 1990s, postmodernism bloomed - sceptical, fragmented, subjective. Some say we’ve now crossed over to the era of metamodernism.

To summarise the latter two terms -

In the postmodernism era of the ‘60s until around 2000, we broke things apart. The trendy tone was ‘irony’. We took existing genres and formats and smushed them together. Post-modernism was Andy Warhol presenting paintings of soup cans, sculptures of brillo cleaning sponges, and block pics of celebrities as ‘high art’. It was the humour of The Simpsons. It was art and culture that referenced itself. It wasn’t just a piece of theatre - it was a Brechtian show where the actors looked out and ‘winked’ at the audience, slyly acknowledging them: “Hi. We know we’re in a play.” (We created a term for this - ‘breaking the fourth wall.’) The pinnacle of postmodernism, Reality TV, was probably inevitable.

Jean Baudrillard was a French philospher who published his most popular works in the postmodern era - the 1970s and 80s. He argued that reality was being replaced by simulacra - copies, or representations of things, that no longer had an original. (Australia’s Gold Coast is a great example, to me, of a city-as-simulacra. Its dominant culture is ‘borrowed fantasy’. Consider some of its suburb names: Miami, Isle of Capri, Sorrento, Palm Beach. It’s home to the most famous theme parks - simulated worlds - in Australia. It nicknamed itself ‘The GC’ when the television show The OC was popular, and it was even home to Australia’s first reality TV hit, Big Brother.)

Beaudrillard believed that we had begun to live in a hyperreality, where simulations (like media, advertising and virtual experiences) were perceived as ‘more real than reality itself’. As a result, he predicted that the distinction between what’s real and what’s not would collapse - or had collapsed already. He imagined that our experience of the world would be increasingly shaped by these illusions, rather than any objective or authentic reality.

Observing where we’re at now, I think he was correct.

Plenty of us have noticed this, and I think that our cultural response has moved us on from the realm of postmodernism. If postmodernism broke the fourth wall, we’re currently smashing up the stage and putting it back together - while filming ourselves doing it. We’re participating while evaluating, aware of the irony but trying for sincerity. In our supersaturated media landscape, commentary itself has even become an art form. We’re in the era of metamodernism now.

A critical part of metamodernism is the meta: watching, sifting, analysing. It’s the aforementioned piece of theatre with that audience wink, but there are more winks and also some serious gazes: you’re not just seeing it live - you’re watching it simultaneously through a screen, plus maybe there’s a little interview with the actors afterwards - and then you post a comment about it online.

Metamodernism oscillates between sincere (modernist) and ironic (postmodernist) tones, and is a response to both. It is a response to the crises of the past two decades, including climate change, financial collapses, and global conflicts. It aims to hold a lot of different viewpoints at once, acknowledge them, and then make a concise point anyway. It’s a reset. We have to pick a side and express it.

Though it’s constantly in flux, metamodernism incorporates both critical analysis and empathy. It accepts cynicism, but adds vulnerability. It acknowledges complexity, but it strives for a more responsible engagement with information.

If that all sounds confusing, picture a pendulum continually oscillating - the metaphor Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker, founders of the webzine Notes on Metamodernism, use to describe metamodernism’s motion. The pendulum swings constantly from the sincere seriousness of modernism to the ironic playfulness of postmodernism. It doesn’t find ‘balance’ - the motion is key:

“Each time the metamodern enthusiasm swings toward fanaticism, gravity pulls it back toward irony; the moment its irony sways toward apathy, gravity pulls it back toward enthusiasm.”

Perhaps this grappling, this swinging pendulum, will eventually lead us back to sanity.

To me, the shadow-banned but brilliant Trump bio pic ‘The Apprentice’ (2024) is an example of a metamodernist film. (I think it should be required viewing for all Americans.)

Let’s start with the events that happened around it in real life - just like in the movie, Trump did the thing he always does when he feels like a loser: he lawyered up. He sent a cease-and-desist to the movie’s producers (but also ranted online about how he wasn’t bothered by it). Consequently, the movie received only a tiny release in the United States - I’m sure that had nothing to do with Trump’s machinations. Anyone who watched it would surely agree that the ethically devoid rapist it depicts should be kept away, at any costs, from the highest position of power in the nation. America elected him anyway.

The entire movie is about the creation of an image, of an outer shell. It lays bare the personal and professional Achilles heel of its subject - he cannot handle the shame of losing. His self-stated motto (which he reportedly stole from Roy Cohn) is, Attack attack attack! Admit nothing and deny everything. No matter what happens, you claim victory and never admit defeat.

That Achilles heel is also, unfortunately, his secret weapon. ‘Can’t handle losing’ is a strength, if you frame it as ‘I’m always a winner’. Some people in real life still choose to believe that this well-documented liar ‘lost the election’ in 2020. They still look up to him as a leader above reproach, quoting the MAGA slogan Trump borrowed from Reagan as if they believe Trump wrote it himself. Even when there’s plenty of information available that lays bare the broken psychology of their hero, these people still choose to stand behind him.

By never delving into his past, and repainting his childhood as ‘great’, Trump has convinced many people that he just walked out of the womb with his ‘winner’ status fully-formed. But just because he doesn’t like to talk about his past doesn’t mean he doesn’t have one - in depicting a once-human Trump desperately attempting to court the favour of his cold, narcissistic father, the film posits a very plausible explanation for why he is the way that he is now. On some level, Trump is still trying to please some invisible father, to crush that enabling mother.

‘The Apprentice’ is sincere - and quite factually accurate - yet its title is an ironic nod to Trump’s facacta reality TV show ‘The Apprentice’. Trump’s TV show functioned as a mythmaking device, an attempt to rebuild his ‘winner’ image after his third bankruptcy, by offering advice on others’ business skills. In the movie ‘The Apprentice’, however, Trump himself is the naive apprentice who grows to usurp his mentor’s cruelty. The movie shows us how he created that ‘winner’ image in the first place.

It winks at us with signature moments it knows we’ll relate to today; Trump holding a Reagan ‘Let’s Make America Great Again’ badge in his palm, paying a journalist who once criticised him to write his ‘Art of the Deal’ book. The movie is layers upon layers of irony and sincerity, but it still takes a damn solid stand.

Here are some other metamodernist things: Childish Gambino’s This is America music video. Most of today’s popular music (glibness juxtaposed with sincerity, samples and genre-smashing). The television show Bojack Horseman - an ageing TV star, sarcastic AF yet sincere. Art installations like these. Amongst the chaos of our current landscape, I hope that the metamodernist conversations we’re having in culture can help us move forward.

Yet I’d like to see us stop chewing our nails to the bone, questioning reality. It is important to question it, but after a while, questioning becomes a distraction from answering - from improving reality.

It’s increasingly important to tune out the noise and engage our critical thinking to sift through facts.

So let’s hurry up and move on to creating ourselves a better reality - before our only entertainment becomes watching chunks of melting ice caps float by.

I hated so called reality TV from the outset. I had a share house when the first Big Brother came out & my housemate Lee had been obsessing about having the TV to herself that night for ages. A special house constructed with cameras in the walls? Nightmarish. Horrific. Why would anyone voluntarily submit themselves to this?

I went out for a walk so I wouldn’t have to be subjected to it. I heard a big cry go up around the neighborhood and when I got back Lee breathlessly informed me about every last thing the amateur actors had done in the show. It was like the invasion of the body snatchers. Everyone had become pod people. Ghastly.

Perhaps as you say its a fifth column into the proletarian brain that bypasses rational thinking. It would not surprise me at all. TikTok is the same and I’ve never watched that either.

Thank you for introducing me to Metamodernism! It's given me a different perspective on what I believe is simply a decay of post-modernism into an endless recycling and reinterpretation of modernist and post-modern cultural products (see: endless film remakes or "reboots", faithful recreations of 20th century musical genres, etc.).

I could be convinced otherwise, but I feel that Mark Fisher really captured the feelings of Gen X and Millennials when he said we were "mourning a future that never happened", because the 20th century promised so much in terms of technology and culture which simply didn't happen. It wasn't a deliberate misdirection though; the compounding growth and the inertia of progress during that period seemed inevitable.

However, in 2025 we have the internet, we have "good enough" medicine to keep us mostly healthy, but capital "P" Progress just stalled.

Out of this cultural (and economic) stagnation has come a retreat into the comfortable, which I argue is in part responsible for the creation of the "Post Truth" world. Uncomfortable truths cause anxiety, and demagogues have been ready and waiting to offer a more "comfortable" world view, where uncomfortable truths are dispatched by safe and familiar ideas, deftly communicated through catchy slogans.